Password hashing considerations

Passwords are typically not stored plaintext in a database. Instead, a cryptographic hash is stored. This makes it possible to check the password, but makes it hard to get the plaintext password, even if the database is leaked. The way the password is hashed affects how hard it is to obtain the plaintext password. In this post we look into what properties a password hash should have.

Attack scenario

Assume we own a web application, where users can login with their username and password. We want to store these passwords securely, even if our database is leaked. In that case, the attacker has access to our password hashes. He wants to obtain the plaintext passwords, for example by using a brute-force attack against the hashes. As defenders, we want to make it as hard as possible for the attacker to brute force the passwords. However, we also want our users to be able to log in, so we want to be able to verify passwords in a reasonable time.

Hardware asymmetry

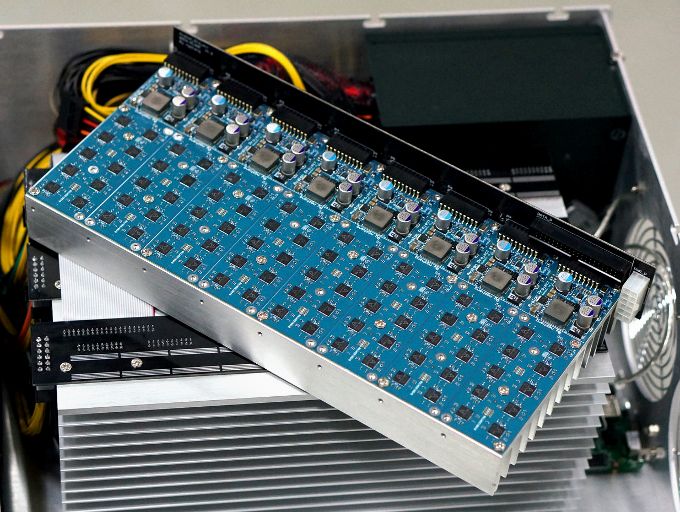

Our web application runs on some commodity hardware, for example on a virtual machine at Amazon. It uses a quite fast CPU, but web servers typically don’t have powerful GPU’s or any hardware acceleration for cryptographic operations. The attacker, on the other hand, can choose which hardware to use to crack our passwords. He can start an Amazon virtual machine with different specs, or start hundreds of virtual machines, or use a computer with a powerful GPU, or even program an ASIC or FPGA to perform the work. By choosing the right hardware, the attacker can reduce the time it takes to brute force the passwords.

When we choose a password hashing algorithm, we want to take this into account. We want an algorithm that runs fast on our hardware, and runs slow on any other hardware. This reduces the advantage the attacker can gain by switching hardware. Normal hashing algorithms don’t have this property. For example, SHA3 is both easy to implement and very fast on hardware. Dan Boneh and his colleagues write the following:

An ideal password-hashing function has the property that it costs as much for an attacker to compute the function as it does for the legitimate authentication server to compute it. Standard cryptographic hashes completely fail in this regard: it takes 100 000× more energy to compute a SHA-256 hash on a general-purpose x86 CPU (as an authentication server would use) than it does to compute SHA-256 on special-purpose hardware (such as the ASICs that an attacker would use).

Using memory

Calculations that are implemented in specialty hardware can be done much quicker than on a general-purpose CPU. However, there is no such advantage in memory. Memory is just as expensive for specialty hardware as for general purpose CPU’s. Thus, when we let our password hashing function use some memory, we reduce the advantage the attacker can gain by using special hardware. Using memory occupies attacker resources, while it is readily available in a normal computer.

This is a pretty old idea, but gained popularity with the introduction of scrypt. Scrypt is basically PBKDF2, with an extra step that uses a lot of memory:

function hash_use_lots_of_memory(in) {

X = in

for i in 0..N {

mem[i] = X

X = hash(X)

}

for i in 0..N {

X = hash(X ⊕ mem[X])

}

return X

}

In the first for loop, it writes a chain of hashes to memory. In the second for loop, it creates a hash based on many of those memory items, in a pseudo-random order. This way, you need memory to store at least N items.

Large word arithmetic

Most calculations can be implemented a lot faster in customized hardware. However, there are also some operations that are well optimized on general purpose CPU’s. Math on 32-bit and 64-bit words is well optimized on general CPU’s. Particularly multiplications are pretty fast on a general purpose CPU, which means that specific hardware doesn’t have a big advantage.

Lyra2, one of the password hashing competition finalists, proposed a cryptographic building block that uses multiplication in order to defend against hardware attacks. They took the Blake2b hash function and replaces addition with multiplication. The result, named BlaMka, is also used in Argon2. The use of multiplications when hashing is an effective way to reduce the advantage of an attacker.

Conclusion

Making an algorithm memory hard or using CPU-optimized arithmetic are two ways to reduce the advantage to an attacker with specific hardware. Modern password hashes like Argon2 take specialty hardware into account, and try to hash passwords in such a way that the attacker doesn’t gain much by choosing his own hardware.